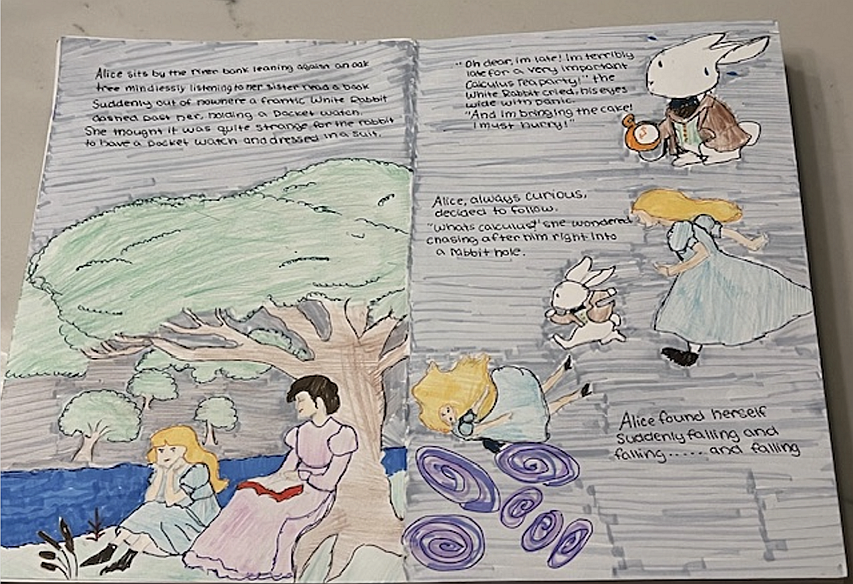

There are two main centers of mathematical investigation of the Wyly Theatre highlighted here.

The aluminum-pipe facade

First, if you walk right up to the corner of the building (the near left corner in the picture above) and (on a bright, sunny day) look straight up at the corner amidst the aluminum pipes which adorn the building, and maybe move your head back and forth a bit, you should be able to catch glimpses of bright sun or sky between the pipes and the building. Why would that possibly be? Why wouldn’t the engineers just fasten the pipes tight to the front of the building? The answer lies in the phenomenon of thermal expansion. For any object, there is a linear relationship between the change in length of the object and the change in temperature. You can find that relationship using what’s called the coefficient of thermal expansion, which is based primarily on the material the object is composed of. You multiply the original length of the object, times the coefficient of thermal expansion, times the change in temperature to get the change in length. For aluminum, the coefficient is approximately 0.0000123 (the units of that coefficient are inverse degrees Fahrenheit, for the record). So let’s try to see how much the pipes might change length between the coldest and hottest day in Dallas.

First, how long are the pipes? They run all the way from the roof of the building, which we can look up to find out is 132 feet tall, to the top of the first story, which we can eyeball to be somewhere in the vicinity of 16-20 feet high. So let’s call the pipes 115 feet long, for simplicity; remember, we are just making an estimate. Since the coefficient of expansion is so small, it will be easier to multiply by 12 to get their length in inches. So let’s use an estimate that the pipes are 1,380 inches long.

Next, what could the temperature swing be from the coldest to the hottest day in Dallas? At the time I first gave this tour, there had recently been a low of 18 degrees Fahrenheit, about the coldest anyone could remember for Dallas. In the summer, though, it can get over 100 degrees easily. So let’s say there could be a 90-degree swing between the coldest and hottest day. Then the pipes might change length by 1380×0.0000123×90 inches, which is approximately 1.5 inches.

That might not seem like much, but imagine if the pipes were bolted to the building at the top and bottom. If the separation between those bolts needed to change by 1.5 inches, it would shear the bolts right off, and there might be pipes falling down around the entrance of the building — not exactly a safe situation. So the architects had to allow the pipes to slide up and down a bit in grooves that keep them close to the building, but do not anchor both ends of the pipe. Those grooves create the space through which you can catch a glimpse of sky. Here we see math being used to keep our public buildings safe.

Now, it’s worth pointing out that the building itself will be contracting and expanding with the change in temperature. So why doesn’t that compensate for the expansion of the aluminum? The answer is that the pipes, being nearly pure aluminum, have a very different coefficient of thermal expansion than other materials used in the building. For example, the coefficient of thermal expansion of glass is only about 0.000003, roughly one quarter that of aluminum. It’s the discrepancy in thermal expansion that would cause structural problems if disparate materials were tightly fastened together.

The ramps down to the lower-level entrance

An immediately striking characteristic of the Wyly Theatre is the elaborate system of ramps and steps leading down to the lower-level entrance to the building. We’ll look at them from a mathematical point of view. Building codes require that each step in a series of stairs have the same height, and the same depth (horizontal distance from the edge of one tread to the edge of the next). That means that with properly constructed stairs, there is always a linear relationship between the distance you move horizontally and the distance you move up or down. That linear relationship is measured with what’s called the pitch of the stairs (or ramp), which is simply the vertical distance traveled expressed as a percentage of the horizontal distance traveled. (In mathematics, this quantity is exactly what’s called the slope of a line, although we don’t usually write it as a percentage in that context.) So let’s try to figure out the pitches of the various features of this entranceway.

The easiest to compute is the pitch of the shallow staircase to the right of the building. You can simply take a tape measure to see that each tread is 6 inches high and 50 inches deep. So the pitch of that staircase is 6/50, or 12%. The steeper ramps must have the same pitch, because you can just see next to the staircase that the surface of the ramp is parallel to a long stick laid on the top edges of the treads — and parallel lines always have the same slope, or pitch.

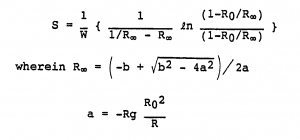

But what about the zig-zaggy more shallow ramp down the middle? What is its pitch? Well, we can measure the maximum height of the low walls which separate one switchback of that ramp from the next; it’s about 32 inches. And we can measure the minimum height of the wall at the other end, it’s about 2 inches. So the ramp drops about 30 inches in one full switchback. Now we need to measure the length of one switchback. Do we measure along the ramp? No, because that’s not the horizontal distance; the ramp is slightly angled. We need to find something horizontal to measure along. Fortunately, there’s a line of re-bar holes on every one of these walls that we can use as a guide to horizontal measuring, and you will find that the horizontal length of each ramp is about 30 feet, give or take. So is the pitch of this ramp 30 inches over 360 inches? No, because as the diagram below shows, one full switchback is two ramps, each 30 feet long, that each drop the same amount. So each one drops 30/2 = 15 inches, over 360 inches, for a roughly 4.2% pitch on these ramps. I think it’s now important to ask why the architects bothered to build this extra zig-zag ramp in the middle. The answer is for handicapped accessibility, and so we see that mathematics is being used to understand and plan for the needs of all to be able to access this civic building. The Texas Accessibility Code specifies a maximum pitch that’s safe for those who need to move about in wheelchairs.

I think it’s now important to ask why the architects bothered to build this extra zig-zag ramp in the middle. The answer is for handicapped accessibility, and so we see that mathematics is being used to understand and plan for the needs of all to be able to access this civic building. The Texas Accessibility Code specifies a maximum pitch that’s safe for those who need to move about in wheelchairs.

(You might at this point ask what that maximum is. Based on the measurements just taken, it’s quite possible you will get suggestions of four or five percent pitch. However, it turns out that the code maximum is 8% pitch. This could spark further discussion as to why, if the maximum was 8%, would the architects have planned such a long ramp only about half the allowed pitch? I don’t know the true answer, but some possibilities that have been suggested are to make the theatre even more welcoming to those in wheelchairs, or because this way the central shallow ramp system divides the entire entrance area into roughly equal thirds, creating a pleasing symmetry to the design. Symmetry is another mathematical concept with strong links to aesthetics and the arts, because most people find symmetry to be inherently attractive.)

There are a couple of other footnotes that we might add here. The shallow ramp travels in a zig-zag fashion. Why didn’t the architect make it straight? The answer is pretty clear; with the required low pitch, if that ramp were straight, it would have to start across the street at the opera house to make it down to the entrance level of the theatre — not a very practical arrangement. What’s interesting here is that a process of folding the ramp up into a zig-zag allowed a longer ramp to fit in a shorter space. Ways that structures can be folded in two and three dimensions are another subject of mathematical study — there is an entire area of mathematical origami — and one with significant practical uses. There are many cases where a large structure must be fit into a small space in a way that will unfold reliably and easily. You can have participants think of such examples; a couple are airbags into your steering wheel or solar collectors for a satellite into the rocket payload bay.

If you’re looking for additional measurements to take, you can examine the pitch of the sidewalk from the street corner up to the side of the building. Is it handicapped-friendly? (It is, but I will leave the measurements that determine its pitch up to you; some creativity is required to get the rise and the horizontal distance for this ramp.)